“Since others may be smart, well‐informed and highly computerized, you must find an edge they don’t have. You must think of something they haven’t thought of, see things they miss, or bring insight they don’t possess. You have to react differently and behave differently.”

– Howard Marks

It has been a year of escalating risk. North Korea sabre rattling, Donald Trump’s tweeting, Catalan separatism, the UK’s muddled Brexit negotiations, and the stock market continuing to set new highs despite everyone knowing it’s “too expensive”. As I reflect on the last twelve months, there is clearly no correlation between market prices rising and the chaos reported in the daily news.

For example, the legislative machine in Washington appears to be even more broken than normal. Their President – under investigation for possible collusion and obstruction – has sent volleys of tweets oscillating between sympathy for white nationalists and reckless sabre‐rattling toward North Korea. Of course, this is the same President that, while on the campaign trail, threatened to start a trade war with China, leading many to assume that global trade would take a hit under his presidency. Instead, the very opposite has happened. In the first half of 2017, world trade grew at its fastest pace in the last five years.

Washington’s dysfunction hasn’t interrupted the continued expansion of GDP and payrolls. Nor has a series of historic natural disasters that ravaged Houston, Florida, the U.S. Virgin Islands, Puerto Rico, and northern California. In fact, while the front pages and homepages of news organizations have been chaotic and dire, the business cycle has been the opposite—steady and positive.

It serves as a reminder that the stock market is not a barometer of moral progress. And it is not a report card on the President of the United States (even if he wishes it were). Investing in the stock market is a wager on the future performance of the nation’s public companies. And they are, to employ a technical term, making a boatload of money right now with corporate profits continuing to set all‐time highs.

And yet, despite plenty of evidence to show the folly of forecasting, many are predicting an imminent correction – largely due to the unwinding of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet with corresponding increases to interest rates. Many financial advisors have been openly sceptical of market prices, diverting client assets into the “crowded” equity income market or, worse yet, illiquid alternative investments. Even institutional investors have been broadly dismissive of public equity markets, using backward‐looking volatility arguments to justify investment allocations to illiquid alternatives like real estate and infrastructure

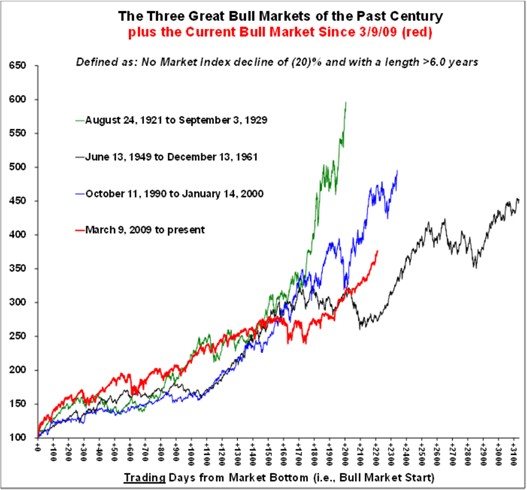

There has been a lot of noise about the current bull market being “unprecedented”. Thanks to a chart provided by Barry Bannister at Stifel (at right), we disagree. The current bull is actually the third longest but only fourth strongest bull market in the past century. Certainly not unprecedented.

John Templeton famously said “Bull markets are born on pessimism, grow on skepticism, mature on optimism and die on euphoria.” At the present time, I firmly believe we continue to be skeptical of public equities. Maturity and euphoria are still in the future. While the bull market continues on, investors have been misled by a continued crowded trade becoming ever more crowded as passive, cap‐ weighted funds continue to gain market share from active management. Until bond yields begin a long‐term ascent, enticing investors to further consider yield‐based equities, the “natural rotation” evident later in a business cycle has yet to come.

The major influence, negative or otherwise, to any bull market is the credit cycle. The credit cycle tracks the expansion and contraction of access to credit over time. It influences the overall business cycle because access to credit affects a company’s ability to invest and drive economic growth. It is easiest to identify cycles by observing the credit spreads and default rates of high yield corporate bonds, which are more pronounced than those of investment grade corporates.

In a strengthening economy, banks increase lending and confidence improves. Leverage begins to rise as higher growth rates lead companies to increase borrowing. As confidence builds, speculative and merger and acquisition activity increases. Typically, toward the end of a cycle, corporate bonds experience heightened price volatility and the credit cycle peaks leading into a recession.

Any recession appears to be a long way off. Global growth remains frustratingly slow, but bright spots suggest that slow positive growth will continue. Both defaults and spreads are low relative to the ends of previous cycles and have actually shown recent declines. These factors suggest we are not yet coming to the end of the expansion phase. To quote the old idiom, “there’s life in the old dog yet.”

The Proper Attitude

Admittedly I tend to be a cynical individual; perhaps that’s a result of my genetics, my personal or social history, or maybe getting hit in the head too many times playing hockey (adding my own credence to concussion theory). But I find, at their core, most of my peers are pessimists as well. I believe it’s a function of our role in managing other’s money ‐ analysing businesses for potential investment. The good analyst never looks at an opportunity solely as potential return, but from the perspective of potential downside risk; or, at the very least, the expected return relative to the potential downside.

Client performance is not driven by outperforming a rising market. The old expression “a rising tide floats all boats” is very true – a rising market will provide any portfolio with price appreciation. But long term sustainable outperformance is only achieved by owning investments that perform well when markets are in decline.

I regularly sit down with students approaching graduation and looking to enter our wonderful vocation. Most profess to have cut their teeth as part of the university investment club. For those readers out there that golf, I draw the comparison to playing in competition versus the weekend game with your buddies. If you really want to test your game’s resilience, play the back nine on the final day of a tournament while in contention. As Dr. Bob Rotella would say, “..there’s no such thing as muscle memory, as memory resides in your head. If your mind is not functioning well, your muscles will flounder.”

What has this to do with investing? Conviction. When the analyst chooses to add an investment to his portfolio, that position will eventually have to be justified to the client whose money is invested. And that discussion will either build trust in the process of the analyst or not. The discussion is even more difficult if the position (or positions) has significantly deviated from the “norm” which can, at times, make the analyst unpopular. It’s far easier to follow trends than to seek out qualities in an investment that are not readily apparent, and to have the conviction in the latter.

So those seeking to join our business should always remember Charlie Munger’s old saw: “I asked a doctor at a medical school why he was still teaching an outdated procedure, and he replied, ‘It’s easier to teach’.” It took me twenty years in the market to understand what I didn’t know and almost another twenty to understand I may never know. It’s simply a lifetime of learning. Market intelligence today is far different than it was in the eighties; the analyst must adapt.

And, of course, one must have the conviction to guide a client properly.

Profiting from the Rollercoaster

The visionary mathematician Benoit Mandelbrot, in his 2004 book “The (Mis)Behaviour of Markets”, comments on investment risk:

“Real markets are wild. Their price fluctuations can be hair‐raising – far greater and more damaging than the mild variations of orthodox finance. That means that individual stocks and currencies are riskier than normally assumed. It means that stock portfolios are being put together incorrectly; far from managing risk, they may be magnifying it. It means that some trading strategies are misguided, and options mis‐priced.”

Further, Benjamin Graham noted in ‘The Intelligent Investor’ that there are two ways an investor can profit by the fluctuation in stock prices; one would be “timing” (the endeavour to anticipate the action of the stock market), and the second is “pricing” (buying stocks for less than they’re worth and selling them for more than they’re worth). Of course, he went on to say that timing doesn’t work for an investor – only for speculators.

To believe stocks can be priced for less than they’re worth the analyst must also believe that markets are inefficient. Of course, to believe that markets are always efficient would assume there is no way to beat the market…and therefore no reason to be an analyst.

The variant here is time. As Graham wrote, “In the short run, the market is a voting machine but in the long run it is a weighing machine.” In other words, sometimes the market prices stocks incorrectly but, over the long run, price and value with ultimately converge.

Procurers of investment management are swayed by short term evidence and largely insignificant statistical data. Returning to Mandelbrot, he co‐wrote an article with Nassim Taleb in which they say:

“Your mutual fund’s annual report, for example, may contain a measure of risk (usually something called beta). It would indeed be useful to know just how risky your fund is, but this number won’t tell you. Nor will any of the other quantities spewed out by the pseudoscience of finance: standard deviation, the Sharpe ratio, variance, correlation, alpha, value at risk, even the Black‐Scholes option‐pricing model.

The problem with all these measures is that they are built upon the statistical device known as the bell curve. This means they disregard big market moves: They focus on the grass and miss out on the (gigantic) trees. Rare and unpredictably large deviations like the collapse of Enron’s stock price in 2001 or the spectacular rise of Cisco’s in the 1990s have a dramatic impact on long‐term returns –but “risk” and “variance” disregard them.”

Unfortunately, “short‐termism” continues to have a dramatic impact on our industry. Recent reports have suggested over $1 trillion have been moved from active management to passive management over the past ten years (since 2006) in the US. The issue is, of course, a more crowded trade into passive products which are riding the bull wave. However, research indicates the investor doesn’t fully understand the risk within the passive product; they are “less informed” according to Michael Mauboussin. He further suggests the movement away from active management is predicated on perceived underperformance against the bull market rise.

In fact, most performance measures of active management refer to public mutual funds which have tended to suffer from too much success. Growing fund sizes force the analyst to buy larger, more efficient (and more mature) stocks with less growth potential. And the mutual fund analyst quickly adopts “herding” to avoid employment risk, resulting in lower deviation among investment results. A quick look at US mutual fund results confirms these beliefs: over any annualized period to November 30, 2017 the SP500 Index has significantly outperformed the average US equity mutual fund manager. In fact, according to Globefund over the past five years, only about a dozen – or less than 1% of the total group ‐ outperformed the index net of fees.

Comparatively, in a September 2017 report, Pavilion Advisors Group report more than 25% of institutional US large cap equity managers outperform the SP500 in the Pavilion universe over five years. And over ten years, more than 50% outperform the index. Those numbers increase significantly when measuring the SP500 against SMID managers (those holding small/mid cap stocks): more than 50% outperform the index over five years and more than 75% outperform over ten years.

So, despite the impressive track record of US index price appreciation over the past ten years, there is clear evidence that active investment managers can outperform. Research shows that fundamental money managers who take a long view and are truly active can deliver excess returns. To quote Mauboussin’s advice, “it is essential to identify a repeatable source of edge and to align the investment process to capture that edge”.

Historical evidence demonstrates smaller managers hold an edge. In 2013, a great article written by Jeff Brown of 18 Asset Management (“David Can Still Succeed”) shows the impact of manager size on returns. Jeff illustrates that managers with less than $1.5billion in assets provided almost 25% greater return over ten years than those with assets above $1.5billion. It’s a well written article and worth consideration by any person thinking about hiring an investment manager.

Which leads me to some final thoughts. The past year has been terrific for our firm. The team has performed admirably in a difficult market environment, developing concentrated portfolios that will provide our clients with prudent growth over the next number of years, regardless of what Mr. Market throws at us.

Once again, we’ve achieved the principal goal of Laurus ‐ to be better today than we were yesterday. Our business has grown by over 30% since I wrote my annual letter at this time last year. We continue to make better decisions by asking tougher questions; of the management teams running the businesses we either own or are considering owning, and of ourselves and our investment process. In the beginning, we referred to this process as taking “the road less travelled”, a reference to taking long‐term, well‐ researched positions. I’m gratified more people are reaching out to us to better understand our process and thank you for your interest.

On behalf of my partners, we would like to thank our extraordinary clients and their advisors for the confidence you’ve continued to show Laurus.

As I’ve said in prior notes, every year end also marks a new beginning. All of us wish you the courage, faith, and strength of spirit to walk the difficult road ahead ‐ along with the tenacity and patience to achieve everything you desire.