I’ve always been a fan of Charley Ellis. He has constantly challenged our industry to be better, criticizing the inability of the investment management business (he prefers to call it a business rather than a profession) to beat the market. He, like many other investors, has a bias for passive investing. He contends that increasing management fees (arguably, he’s referring to mutual funds here) and shrinking returns spell the end of “active” management.

“As indexing repeatedly earns higher returns at lower cost and with less risk and less uncertainty, the world of active management will be taken down, firm by firm, from its once dominant position.”

Charley Ellis, Founder, Greenwich Associates

I’ve always been a fan of Charley Ellis. He has constantly challenged our industry to be better, criticizing the inability of the investment management business (he prefers to call it a business rather than a profession) to beat the market. He, like many other investors, has a bias for passive investing. He contends that increasing management fees (arguably, he’s referring to mutual funds here) and shrinking returns spell the end of “active” management.

To be sure, much of Charley’s argument has merit. Forty or fifty years ago, there were few university graduates that went into the investment community. Now, according to the CFA Institute, there are over 142,000 members in 159 countries with an additional 4,250 currently participating in their 2016 research challenge. Ellis’ also contends that since all these people have the same kind of computers, the same kind of data and information, and the same types of securities analysis, it’s impossible – or incrementally more difficult – to beat the next guy.

Recently, Seth Klarman, who manages about $30 billion with the Baupost Group, noted that “one of the perverse effects of increased indexing and ETF activity is that it will tend to lock in today’s relative valuations between securities….Thus, today’s high‐multiple companies are likely to also be tomorrow’s, regardless of merit, with less capital in the hands of active managers to potentially correct any mispricings.”

That’s an interesting thought. In essence, Klarman suggests that increased indexation will increase the efficiency of the market to the detriment of investors. And, as a corollary, those stocks not in the index will be further mispriced (or inefficient) as fewer investors participate.

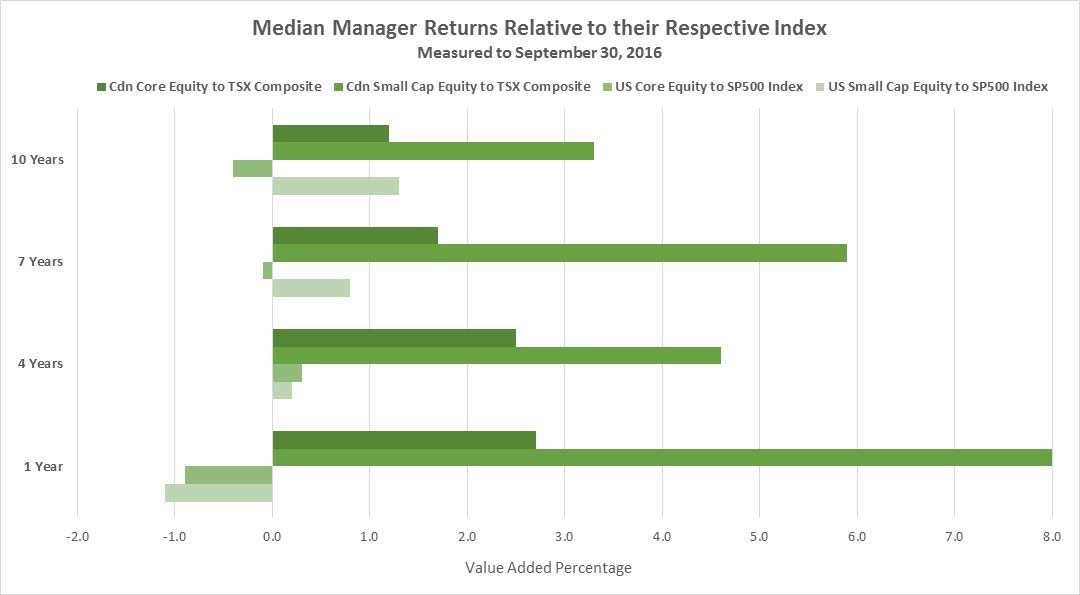

But is Ellis’ argument even justified? We utilized the large international dataset of institutional managers kept by Pavilion Advisors (Montreal) to assess whether the industry earns their fees. The chart shown seems to contradict his contention.

Admitting up front there is some imbedded survivorship bias, the only index an “average” manager doesn’t outperform consistently is the SP500 index. That’s not surprising given it includes many of the best companies in the world to invest in and is, therefore, highly efficient. And, not surprisingly, small cap managers consistently outperform their larger cap counterparts (and, properly invested, with lower volatility).

Apparently the active manager is still alive and well, providing solid value added returns for their clients. Sorry Charley.